Define the Terms

Tank Irrigation in Sri Lanka

Tank

“Tank is a man-made rainwater harvesting unit especially for irrigation, constructed by an earthen dam with other technical devices, across an ephemeral rivulet or stream within a micro/sub-basin”.

Tank Classification in Sri Lanka

- Small Tanks (0-80 ha. of Irrigated Aria)

- Medium Tanks (80-400 ha. of Irrigated Aria)

- Large Tanks (More than 400 ha. of Irrigated Aria)

- (Agrarian Service Act, 1979)

Below 200 acres of Tanks and Anicuts under the “micro irrigation units” administrated by the Agrarian Service Department. (Others belong to the “Major Irrigation” administrated by the Irrigation Department)

- (Agrarian Service Act, 1979)

Irrigation Tank

Tank built especially for Irrigation purposes. (It is different from a ‘Lake’ which is an artificially modified water body, but not essentially for Irrigation. Ex. Bere Lake, Gregory Lake, Kandy Lake)

Village Tank (Gam wew)

Tank with a village. The respective villagers cultivate the irrigation command area and obtain the water from the tank under the supervision of ‘wel vidane’.

Olagam Wew

Tank without a village. However, all the tank irrigation devices such as ‘Sluice’, ‘Spill’, ‘Canal Systems’ are there.

Kulu wew

Sediment Trapping Tanks, established covering the upper tributaries of medium or large scale tanks, in the Dry Zone. No irrigation devices were established except a ‘Spill’.

Tank Cascade

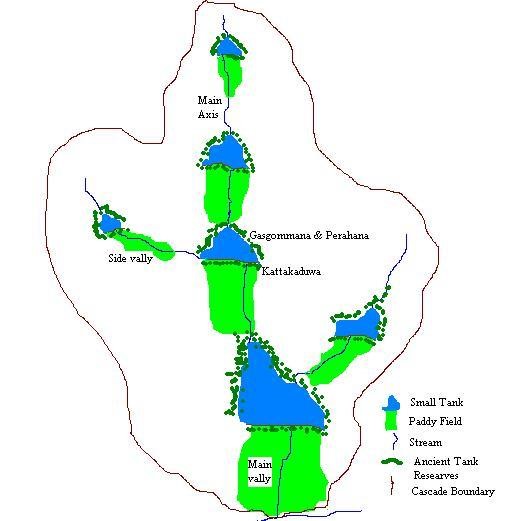

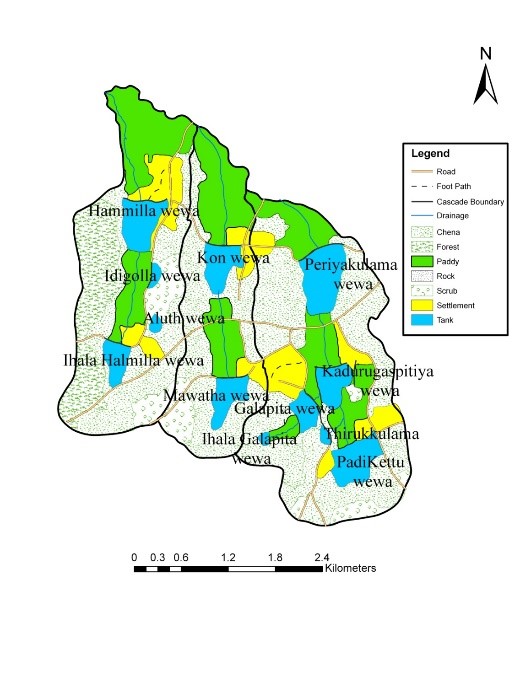

“Connected series of tanks with its’ micro catchments and command areas, organized within a small valley”.

Note: “Tank Cascade” is not only the cascaded tanks along a stream. The entire catchment and command areas and their bio-physical-human environments belong to the cascade area. Cascade naming should follow the name of the last tank or the largest tank of the cascade.

Tank Cascade Cluster

“Adjacent tank cascades, according to the geomorphological setting”.

Note: Within a single river basin, a few cascade clusters can be identified.

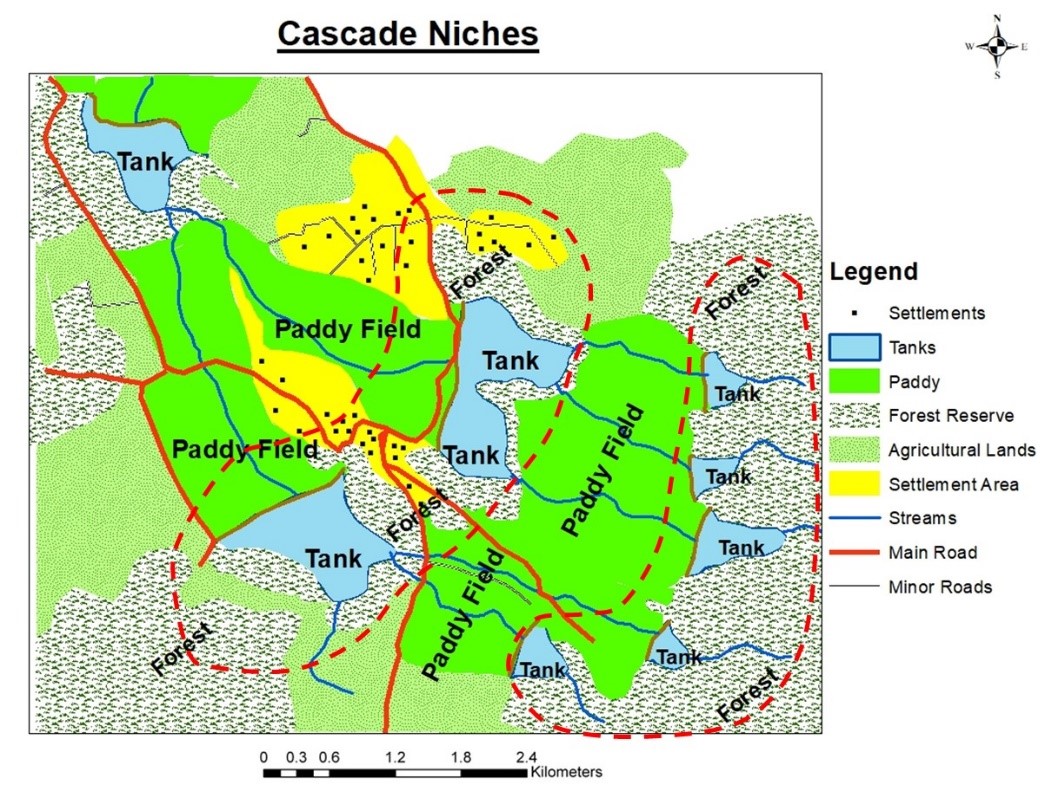

Tank Cascade Niches

“Horizontally integrated ethno-ecological zones in Tank Cascades”.

Note: Within a tank cascade or among the tank cascades there may be ‘horizontally integrated ethno-ecological zones. These zones may contain more biological movements or interactions, as well as human relations. A few researchers attempted to identify these zones as ‘Cascade Ensembles’. However, instead of this term, the proper identification may be the “Cascade Niches” in the aspect of zonation of biological and human interactions or movements.

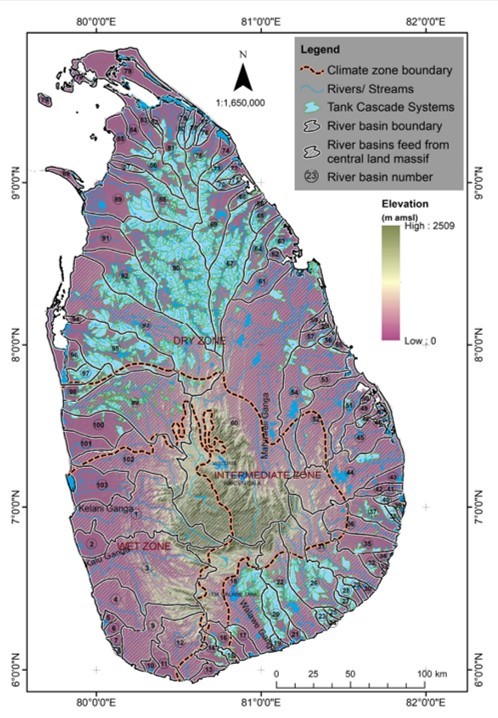

Distribution of Tanks and Tank Cascade Systems in Sri Lanka

Geographical Distribution

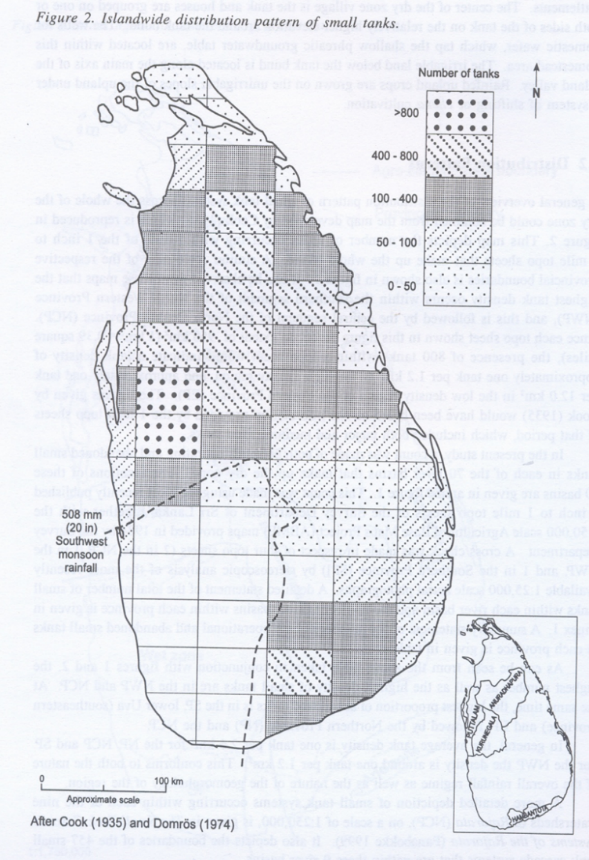

The geographical distribution of tanks in Sri Lanka was studied by Cook (1935) long before when she continued the same studies as the first Head of the Department of Geography at the University of Peradeniya. She has developed a spatial map to show the tank density in different regions within the island (Figure 8). Two third of the country has been covered with tank environments, while the highest density records are in the western dry zone due to the availability of too many small tanks following the geomorphological background.

Tank Cascade-Based Studies

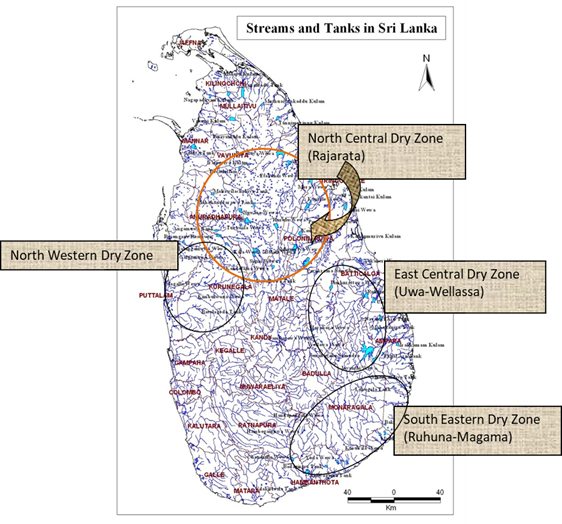

When it comes to tank cascade-based studies, Panabokke et al. (2002), and Rathnayeke, et al. (2021), attempted to figure out the available number of tank cascades and roughly identified 1,200 Tank Cascades are there. However, the majority are situated in the North Central dry zone of Sri Lanka (Figure 9).

However, it could be identified four major tank cascade Regions in Sri Lanka as follows (Figure 10).

- North Central dry zone

- East Central dry zone

- Southeastern dry zone

- Northwestern dry zone

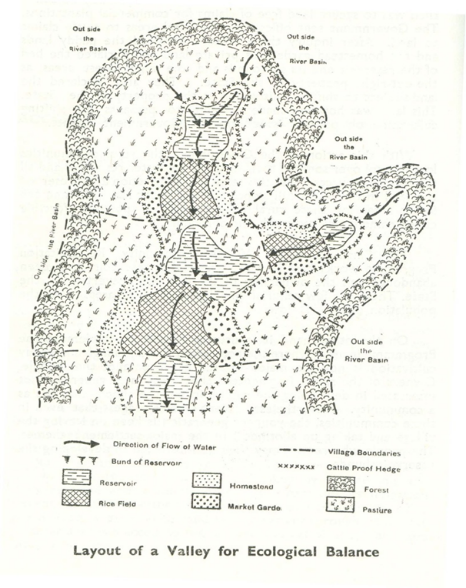

Ecological Components of TCS

The first attempt at the biological analysis of the tank was Ratnatunga’s (1970) “Eco-Village” concept to describe the Ecological/Biological status of tanks in the dry zone areas in Sri Lanka (Figure 12).

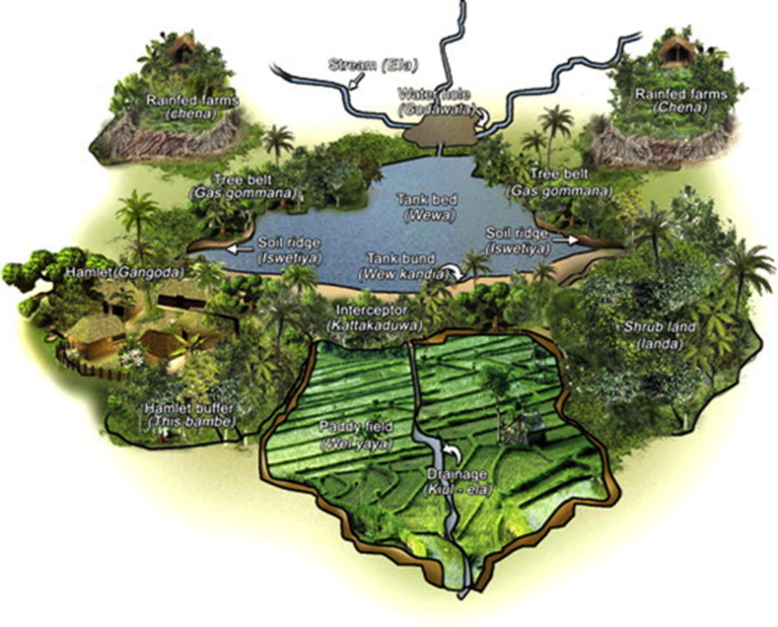

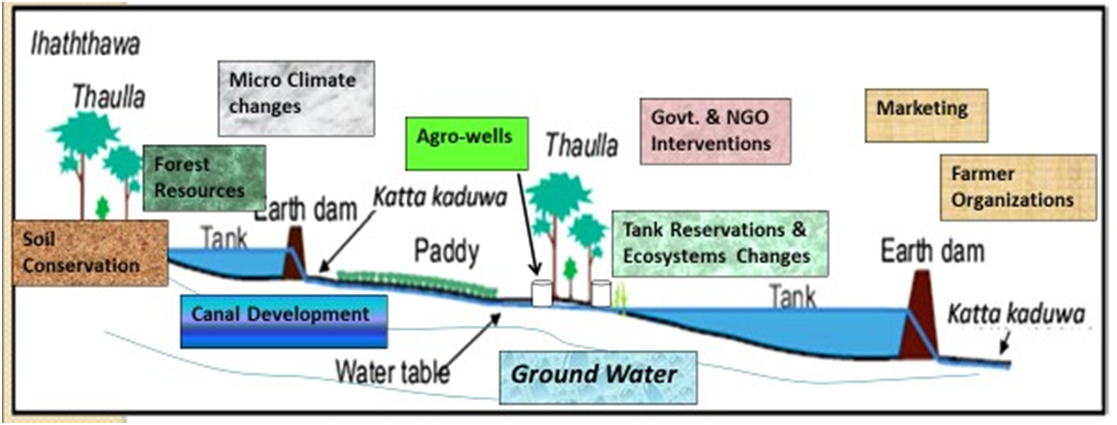

Madduma Bandara (2010) explained that “the traditional village tank systems in Sri Lanka support biodiversity as they provide mixed, heterogeneous landscapes: small tanks, irrigated paddy fields, forests, and villages in small areas”. All the tank systems consist of their own unique ecosystem, flora and fauna, and indigenous knowledge that fulfill a unique function within the system (Dharmasena, 2010). Further, he produced a model to represent the ecological behavior in the vicinity of tanks (Figure 13).

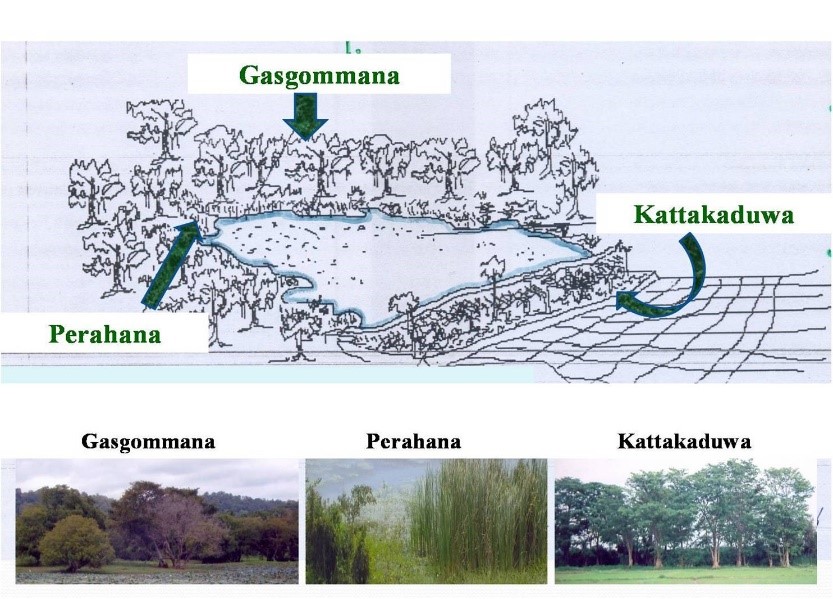

The tank reservations around the tanks, especially “Gasgommana”, “Perahana”, and “Kattakaduwa” play a significant role in the sustainability of the tank as well as maintaining the biological diversity in the dry zone. Perera (2010) conducted a thorough analysis of these reservations and their biological contribution to the environment.

- Gasgommana: It is a strip of large trees located in the tank catchment, just above the water level of the tank serves as a windbreak, thus reducing evaporation losses. Between 10 - 20 % of the tank water surface in the immediate periphery of a tank are covered by this tree zone. This zone is very important to reduce the potential evaporation from the tank surface in the dry season.

- Perahana: A strip of bushes that acts as a filter and prevents eroded soil from agricultural lands in the catchment. This silt trap plus the Kulu-wewa system are one of the secrets behind the long period of less siltation of these ancient tanks.

- Kattakaduwa: A reserved land strip with well-rooted trees located between the tank bund and the paddy field. This plot of land helps to prevent water with salts from seeping into the paddy fields and minimizes water seepage through the tank bund. Further, this zone acts as a salinity interceptor belt by minimizing the salinity impact on the command area.

Marambe and Geekiyanage (2012) further explained the ecological contribution of these tank reservations in the dry zone landscape. The tank ecosystems play a vital role such as maintaining biodiversity, wild fruits, protecting herbal plants, and supplying handloom materials including mat-grass and rattan in addition to maintaining the water source-based habitat units for several fauna species.

Socio-economic Aspects of TCS

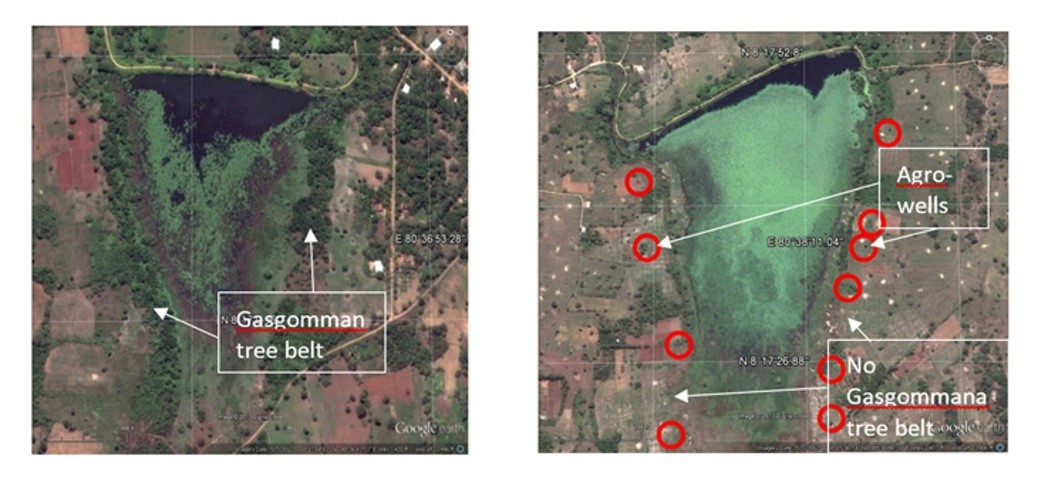

With the evolution of dry zone resource management in Sri Lanka, these dry zone tank cascade systems have been transforming into more interventioned, efficient, as well as vulnerable zones. Crop diversification, animal husbandry practices, home garden development, and marketing interventions have arrived at the tank cascades. In addition to that, a new groundwater usage pattern based on agro-wells and tube wells has arisen. The agricultural production especially in vegetable farming and spicy crops including chili and ginger has been popularized in these tank cascade areas using the groundwater in the dry season. With these changes in water usage patterns, ancient tank cascade systems have been converting to surface water plus groundwater mixed usage patterns with technological advancements.

Current Status of the Tank Cascade Systems

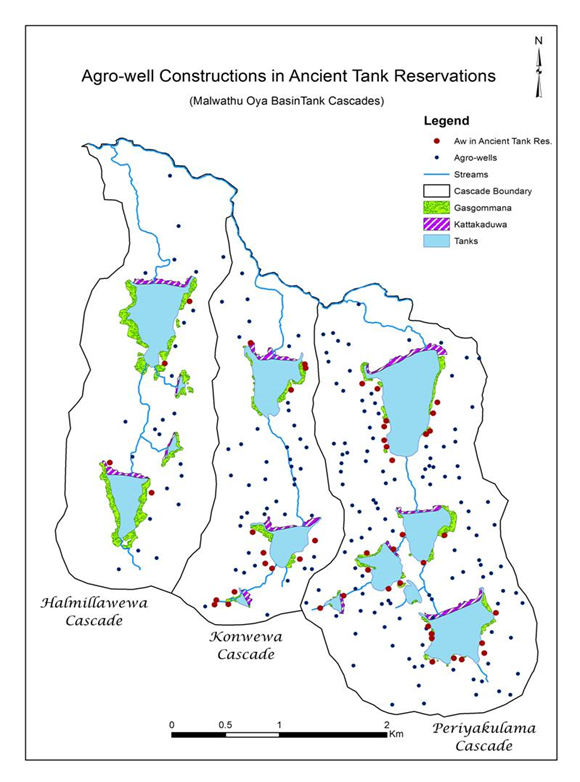

Currently, tank ecosystems are being degraded due to increasing population, increased demand for land, increased construction, and increased demand for wood and firewood. The tank reservation areas are being transformed into agricultural land. Hence, with the natural environmental degradation, there are no bees inside the tank reservations today. There are no places where birds are making nests. Many irrigation-related traditions are fading away. Ecologically, nitrogen cycles, and phosphorus cycles rarely operate in the vicinity of tanks. The challenge today is whether these ecosystem features can be rehabilitated as in their original shape. Tank reservations have become other land uses. According to a study conducted by Perera (2016), covering 20 tank cascades in the Malwatu Oya Basin and Yan Oya Basin, the tank reservation damages have been the most significant biological change in tank cascade areas recently (Figure 16 & 17).

In addition to that, microclimatic changes, groundwater flow changes, ecosystem sustainability issues, the emergence of new land uses, and the fading away of the unique irrigation technology, have created an unhealthy context of these thousands of dry zone wetlands which were historically created by our forefathers (Figure 18).

With that context, the challenges of these tank irrigation systems cannot be underestimated because the 'irrigation environment' reflects the cultural profile of the past irrigation heritage, and the proud history of the ancestors of the island Sri Lanka.